Creative Destruction Inside The Firm

An ephemeral group is a coalition that comes into existence for just enough time to pursue an opportunity and then dissolves. Ephemeral groups can be formed within a larger organization or from a set of individuals with little previous knowledge of one another. A major impediment to ephemeral groups are setup and teardown costs that occur when forming and dissolving the group. These costs are described here as friction.

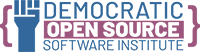

Creative Destruction

In his book ‘Built to Last’1, Jim Collins describes a list of features that organizations must posses in order to stand the test of time. Tom Peters, in his book Re-imagine!2, offers a rebuttal to Jim Collins that amounts to some organizations should *not* stand the test of time. This is to say Tom Peters and others seem to believe that the best thing for some entities to do is to die, and have their resources reallocated. Josef Schumpeter3 calls this the process of creative destruction. We can isolate three main reasons why new organizations (or coalitions) should emerge and old organizations should die (instead of evolving and surviving). These three reasons are summarized as innovation, empires, and inefficiencies.

Innovation

In the Innovator’s Dilemma4, Clayton Christensen identifies what he thinks is the main problem with innovation in large organizations.

1. Good management obeys customer desires

2. Customers desire more of the same

3. Therefore, good management obeys the desire for more of the same.

This would mean that autonomy from ‘good management’ is required for innovation. The

innovator’s solution5 includes examples of ways to divest or create a totally separate organization which would be unimpeded by the parent organization.

Empires

In his book Power, Empire Building, and Mergers6, Steven Rhoades says economists overlook the draw of power when considering incentives for companies. Most economists only consider the profit incentive when modeling the incentives for organizations. Power is not easily modelled, and so evades some economist’s view. He goes on to make a distinction between monolithic capitalism and competitive capitalism. Competitive capitalism uses markets as the key indicator to find which organizations are the fittest. Monolithic capitalism gives the pursuit of power a key role in the fitness of organizations.

Organizations pursue power, or indulge in empire building, in order to increase longevity while circumventing market forces. When an organization pursues power instead of innovation, it creates winner take all situations that may take the form of monopolies. For example, organizations can create inefficiencies by relying on empire building to superficially lock in customers through the use of political power instead of creating innovative products and services.

In the economics of strategy7, Besanko et al. discuss ‘lobbying costs’ which are the opportunity costs associated with internal units within organizations that excel at lobbying. This allows them to obtain more resources from some central planning unit than is merited by performance. Lobbying is another form of power that allows an organization to continue to exist despite being inefficient.

Inefficiencies

The inefficiencies of large entities can be measured by comparing the allocation of resources with a distributed organization with similar resources. The problem can be characterized as centrally planned resource allocation versus market resource allocation. If an internal unit that would merit some resource is denied that resource because of monitoring costs associated with inadequate information at the central planning level, the larger organization would be better off letting autonomous smaller organizations form and measuring the performance of these smaller organizations.

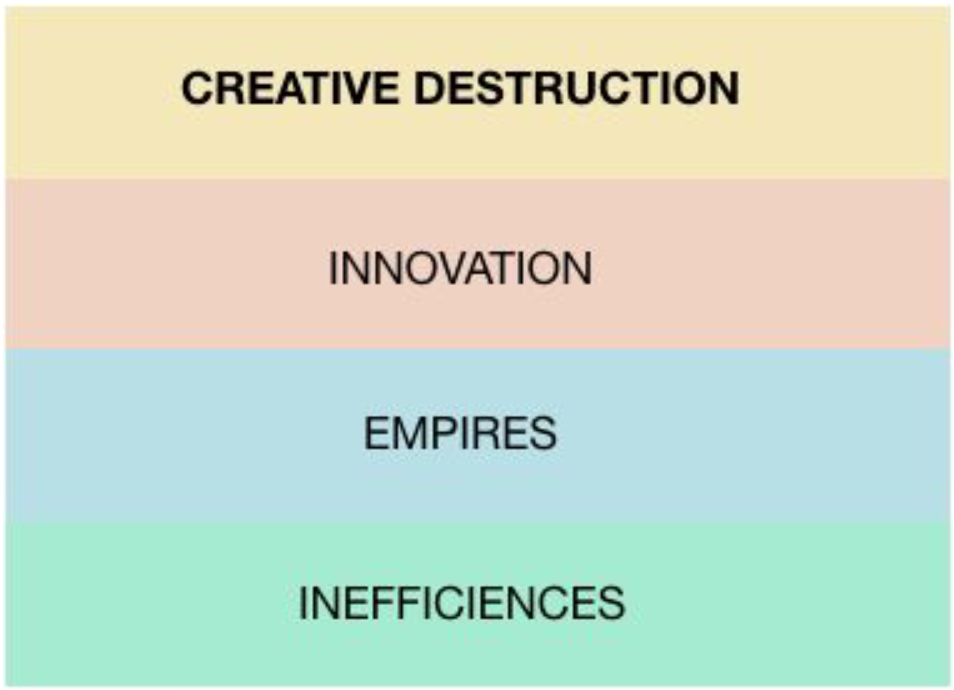

Free Agents

In the year 2000 there were 33 million ‘free agents’ in the united states alone8. This accounted for 30% of the workforce9. On top of this, Andrew Jones identified at least six new types of work that have become increasingly popular in the United States in the last decade10. These are distributed work, flex work, remote work, project based work, and coworking. Together these facts point towards a fundamental shift in how work is performed.

Friction

The popularity of individuals operating as free agents gives rise to the question: when does it become advantageous to form a group? We can refer to any impediment to forming a coalition of free agents as friction. Self organization is the process of small components coming together without a central planner.11 The first form of friction seems to be coordination itself, if there is no designated central planner. Another major inhibitor for forming a self organized coalition seems to be the monitoring costs associated with the allocation of resources.12 Ronald Coase identifies search costs as the primary reason why firms form,13 which also seems like the reason free agents would form coalitions. In other words, it is more expensive for potential customers to ‘find’ multiple free agents and assemble them than it is for a customer to ‘find’ a single coalition. It seems friction should also be a function of search costs.

Autonomy

Autonomy has been noted as a key factor in motivation of agents in Daniel Pink’s book Drive. Since autonomy is becoming more demanded by labor, those agents that are autonomous and but still self organize in order to complete larger projects should be more competitive.

External Markets

Given the importance of human capital in a service based economy, when considering a coalition of agents in the workforce one should distinguish the internal market of labor from the external market of consumers. If an organization is able to control the internal market with superior incentives that promote mastery, autonomy, and are purpose based, it can use that superior human capital to capture those external markets that are becoming more on demand in nature. There are strategic costs that affect the flow of information from the external market to the internal structure and decision makers of the firm. High volume or complex information flows from various inputs or learning costs associated with rapid technology changes can be extremely expensive as Besanko et al. say:

“The reorganization of Pepsi in 1988 illustrates how demands for faster information processing driven by changes in the external business environment can overwhelm a hierarchy … When faced with requests for promotions or special pricing deals by a supermarket chain … disputes were then funneled to … the head of Pepsi USA … this impaired Pepsi’s ability to respond and put it at a competitive disadvantage””14

These types of information flows fit well with smaller, autonomous groups that can react to information or technology changes because they are closer to the problem.

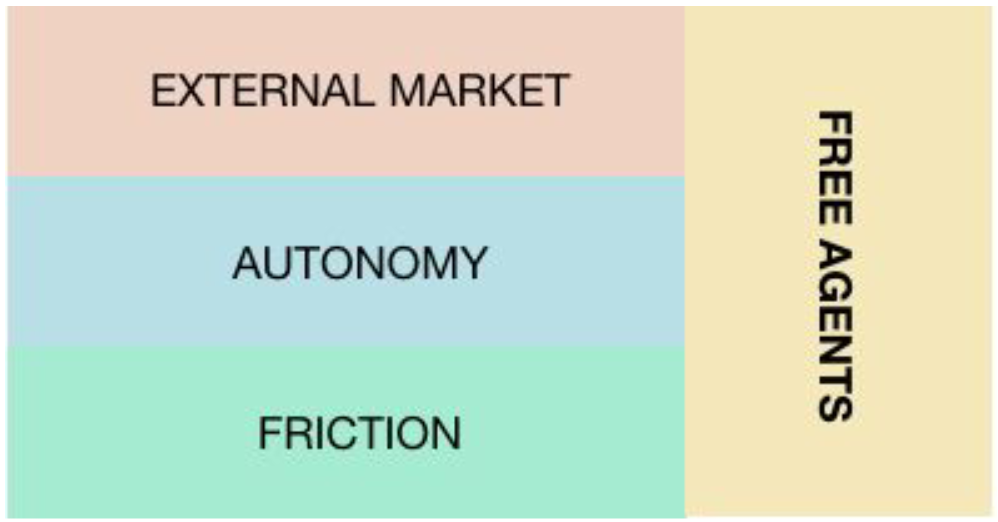

Coalition Formation

One way to look at the capturing of project work is as a cooperative n player game where the goal is to acquire a multi-person project. The formation of a coalition (when parties have similar levels of power) is usually the best way to ‘win’15 (or get a payoff from 16) a cooperative n-player game.

Efficiences

Cooperation can have positive or negative outcomes. Positive cooperation results in efficiencies from economy of scale and scope. Negative cooperation can be thought of as collusion and results in a greater gain for the colluding group but circumvents markets. It is an agreement among firms or individuals to divide a market, set prices, limit production or limit opportunities17. Empire building can involve colluding to superficially limit opportunities to those with special access. The external market becomes less efficient with negative cooperation as noted by Adam Smith.18

Network Organizations

One form of small unit cooperation that has been observed within current corporate structures is called a networked organization. David Besanko describes a networked organization as one in which control is split into profit and responsibility centers. As the number of these smaller centers increase, large organizations struggle with the problem of how to organize across profit centers who may have different or competing incentive systems. Network organizations coordinate by elevating the focus of the individual or worker groups above the tasks they accomplish. Besanko says:

“The basic unit of design in the network structure is the worker rather than the specified job or task … networks develop from the patterned relationships of organizational subgroups”19.

Profit Centers

Profit centers are worker units that can make revenue in the market. If one individual can successfully bill the market directly, that individual is a profit center. Groups of free agents can get together to complete projects that an individual may not be able to do alone. Furthermore, if there is a minimal amount of friction during the start up and tear down of the coalition, the group can temporarily form the coalition, complete the project, and then dissolve the coalition while still showing a profit. The less friction the coalition has when forming, the more opportunistic the coalition can afford to be.

Serendipity

Creating affordances for ephemeral groups to form promotes serendipitous situations. Here are four examples of environments that are conducive to ephemeral group formation.

Module Organizations

Besanko et al. describe how modular network organizations operate as:

“… a type of network structure that involves relatively self contained organizational subunits tied together through a technology that focuses on standardized linkages. Most of the critical activities for a modular subunit are contained within that unit, and links with the broader organization are minimized.”20

So module based units can pursue any opportunity that has standardized on a specific protocol or technology. When the opportunity presents itself within the larger network organization, the smaller module unit can pursue that opportunity while retaining economies of scale or scope. The coalition within the unit does not dissolve but the coalition between the module unit and the greater network organization may dissolve per specific opportunity.

Devops Philosophy

Within information technology, the movement known as DevOps has contributed to reducing friction for ephemeral groups. The philosophy of DevOps is to make repeatable, reliable, and predictable systems. One effect of having a system with these properties is it reduces the cycle time of getting a system up and running. Getting environments anywhere, anytime reduces risk and is conducive to experimentation, which empowers teams. For example, an empowered software team with superior DevOps assistance can innovate more by creating new project alternatives without risking the critical function of the software being developed. An ephemeral group in the form of a cross functional team drawn from different software projects can do an experimental code spike with little risk to timelines or code bases.

Microservices

Martin Fowler describes a microservice21 as:

“… an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery.”

Microservices are the software counterpart to the module organizations referenced previously. Just as human module units can pursue opportunities without excessive coordination within the umbrella network organization, microservices:

“ … are independently deployable and scalable, each service also provides a firm module boundary, even allowing for different services to be written in different programming languages. They can also be managed by different teams.”

This is in contrast to monolithic systems where:

“… change cycles are tied together a change made to a small part of the application, requires the entire monolith to be rebuilt and deployed. “

Microservice development is an example of the technical reduction of friction because a team can contribute to or compose many microservices without having to develop in lock step with other teams.

SAP Partners

Besanko et al descript SAP consulting partners as autonomous groups with ephemeral properties:

“A similar network structure developed in SAP AG … one of the world’s largest software producers … To accomplish its growth objectives, SAP has developed a network organization of partners, who perform 80 to 90 percent of the consulting implementation business generated by SAP products.”22

The partners in SAP’s network operate as autonomous profit centers with SAP AG as the resource (product) owner in a stratified selfo rganized group. Any partner has the ability to generate consulting work, autonomously, without direction from SAP. SAP also does not have to micromanage the consultancy but rather can let the market decide if the partner is delivering valuable services or not.

Summary

As the workforce becomes more autonomous ephemeral group environments should be promoted in order to take advantage of markets with increasingly complex information flows that are too difficult for traditional hierarchies to manage efficiently. Any impediment to formation of a group which intends to capture a section of the market or provide a unique internal business capability is inefficient, but is difficult to avoid given the problems of empire building and the subversive effects of lobbying. The real world examples of module organizations, the DevOps movement, microservice architecture, and the SAP partner network organization seem promising but the future of even smaller and more autonomous ephemeral group formation remains unclear.

- Collins, J. C. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap … and others don’t. New York, NY: HarperBusiness.

- Peters, T. J. (2003). Reimagine! :. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1950). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper.

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: The revolutionary book that will change the way you do business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Christensen, C. M., & Raynor, M. E. (2003). The innovator’s solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Rhoades, S. A. (1983). Power, empire building, and mergers. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Besanko, D., Dranove, D., & Shanley, M. (2000). Economics of strategy. New York: Wiley.

- “With 16.5 million soloists, 3.5 million temps, and 13 million microbusinesses, our “very near the truth” total is 33 million free agents.” Pink, Daniel H. (2001042 6). Free Agent Nation: How Americans New Independent Workers Are Transforming the Way We Live (Kindle Locations 693694 ). Grand Central Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- “… puts the free agent figure at about 30 percent of the American workf orce.” Pink, Daniel H. (2001 04 26). Free Agent Nation: How Americans New Independent Workers Are Transforming the Way We Live (Kindle Locations 696 697). Grand Central Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- Jones, A. M. (n.d.). The fifth age of work: How companies can redesign work to become more innovative in a cloud economy.

- “… a process in which pattern at the global level of a system emerges solely from numerous interactions among the lower level components of the system. Moreover, the rules specifying interactions among the system’s components are executed using only local information, without reference to the global pattern.” , Camazine, Deneubourg, Franks, Sneyd, Theraulaz, Bonabeau,SelfOrganization in Bio logical Systems, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0 691 11624 5 ISBN 0 691 01211 3 (pbk.) p. 8

- Self Organized Resource Allocation, W. Watson, 2016.

- “The main reason why it is profitable to establish a firm would seem to be that there is a cost of using the price mechanism. The most obvious cost of ‘organizing’ production through the price mechanism is that of discovering what the relevant prices are. This cost may be reduced but it will not be eliminated by the emergence of specialists who will sell this information. The costs of negotiation and concluding a separate contract for each exchange transaction which takes place on a market must also be taken into account”. Coase, Ronald (1937). “The Nature of the Firm”. Economica (Blackwell Publishing)4 (16): 386–405.

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko et al., 4th ed., p.527

- “Some solutions aim at reaching an arbitration point based on the strengths of the players. Others try to find equilibrium points such as exist in a market of buyers and sellers. Some define a solution as sets of possible outcomes satisfying certain stability requirements.” Davis, Morton D. (20120 73 1). Game Theory (Kindle Locations 24822 483). Dover Publications. Kindle Edition.

- “The AM theory does not attemp t to predict which coalition will form; its purpose is to determine what the payoffs would be once a coalition is formed. “ Davis, Morton D. (20120 73 1). Game Theory (Kindle Locations 2674 2675). Dover Publications. Kindle Edition.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collusion

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Competition_law#Classical_perspective

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko et al., 4th ed., p.522

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko et al., 4th ed., p.523

- http://martinfowler.com/articles/microservices.html

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko et al., 4th ed., p.531

Copyright © 2016 W. Watson, All Rights Reserved