The new way to work in the sharing economy

Some professionals do not believe self-organized groups are possible or, if possible, efficient

enough to endure as a valid corporate structure. Camazine et al.1 describe self-organization as:

“… a process in which pattern at the global level of a system emerges solely from numerous

interactions among the lower-level components of the system. Moreover, the rules specifying

interactions among the system’s components are executed using only local information, without

reference to the global pattern.”

For our purposes we will describe a self-organized group as a group with no central planner.

What does a self-organized group look like? How does it behave? What are its benefits? In order to answer this questions we must first investigate how self-organized groups form in the first place.

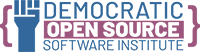

Self Organization -> Autonomy Continuum

The path to self organized groups can be described as a continuum that spans from least autonomous to most autonomous. The antithesis of a self-organized group is a hierarchy with a central planner that has complete authority through owning all resources. A good example of this kind of hierarchy is found in English feudalism2. In contrast to a central planner who creates a hierarchy as in feudalism, a republic is3 a form of self organized hierarchy. A republic organizes by electing a central planner. The difference between a republic and feudalism is the power in a republic still lies with the general population. A good example of a self-organized group which is a republic would be the Mondragon cooperative from Spain. As William and Kathleen Whyte describe:

“The structure of the Mondragon cooperative … vests ultimate power in the general assembly of the cooperative in which all members of the firm have not only the right to vote but the obligation”4

The second type of self-organized group is a stratified (or more accurately, pre-stratified) group of insiders and outsiders. A stratified group can form when first movers arrive at a valuable resource site and establish a claim to a resource. If outsiders behave in such a way that is autonomous concerning their day-to-day operations, they are self-organized. The defining characteristic here is the resources are owned by the insiders who bestow rules (notably a rent) on outsiders with respect to the resource. Gregory K. Dow and Clyde G. Reed give an example of this using the self-organizing societies that formed during the California gold rush.5 During the gold rush the first-moving land owners (insiders) claimed valuable land while a pre-stratification period formed when the secondary-outsider population (miners) came in and mined the land. The first and secondary populations followed only natural incentives6 in deciding where to lay claims and mine, but there was some central planning via the rules6 issued by the resource-owning insiders. Miners (outsiders) were free to claim any unclaimed valuable

land if found. At the point that all land is claimed, the relationship turned into an elite-commoner relationship where all power is completely in the hands of the insiders (now called elites) which then, because of the new power dynamics, inherently diminishes the act of self organization.

The third kind of self-organization is a pure self-organization with no insiders that manipulate decisions based on resource ownership. These self-organized groups must emerge completely based on natural incentives with no central planning. Some examples of non-hierarchical self-organization with no insider/outsider relations are the Underground Railroad7, free markets in capitalism, and the Request7 for Comment (RFC)8 system for internet standards9.

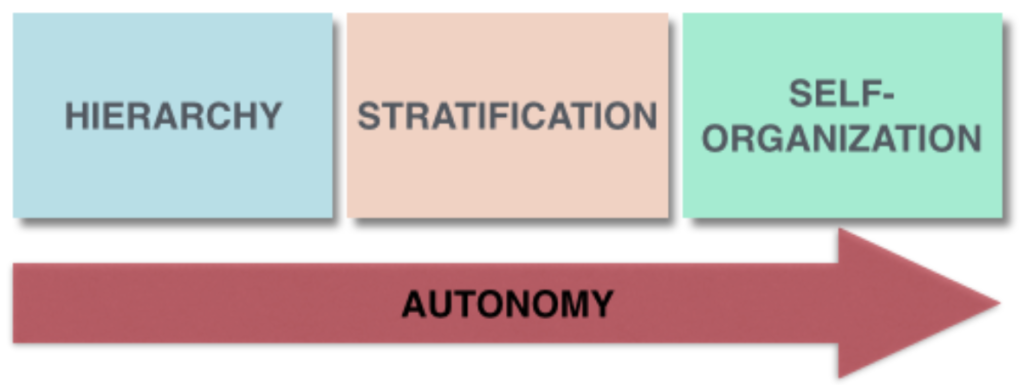

Organic Structure -> Economic Drivers

By examining economic drivers of search costs, strategic costs, and innovation incentives we can better understand how self organized groups emerge. Search costs are explored best by Ronald Coase when describing why firms emerge at all:

“The main reason why it is profitable to establish a firm would seem to be that there is a cost of using the price mechanism. The most obvious cost of ‘organizing’ production through the price mechanism is that of discovering what the relevant prices are. This cost may be reduced but it will not be eliminated by the emergence of specialists who will sell this information. The costs of negotiation and concluding a separate contract for each exchange transaction which takes place on a market must also be taken into account”.10

That is to say without search costs there would be no firm, self organized or otherwise, but rather only individuals interacting directly with markets. A self organized firm must satisfy the reduction of search costs of its main productive function for its customers.

Strategic costs are costs associated with the processing of the flow of information from the external environment into the internal structure and decision makers of the firm. High volume or complex information flows from various inputs or learning costs associated with rapid technology changes can be extremely expensive as Besanko et al. say:

“The reorganization of Pepsi in 1988 illustrates how demands for faster information processing driven by changes in the external business environment can overwhelm a hierarchy … When faced with requests for promotions or special pricing deals by a supermarket chain … disputes were then funneled to … the head of Pepsi USA … this impaired Pepsi’s ability to respond and put it at a competitive disadvantage””11

Although some economists and historians like Alfred Chandler believe structure follows strategy , and12 others like Thomas Hammond13 believe structure influence strategy, all seem to believe there is a strong correlation between the two.

Good Management ~ Innovation

Innovation incentives are the drivers for individuals or groups within an organization to innovate. Innovation incentives are typically managerial incentives such as stock options, there are inherent problems with these types of incentives, not least of which is the adoption of short term strategies over long term ones. The phrase ‘the innovator’s dilemma’14 was coined by Clayton Christensen to describe the problems of management (i.e. central planning) and innovation. A summary of the dilemma is that good management tends to give the customers what they want and customers tend not to want new, innovative things but rather more of what they have already. One solution offered to the innovator’s dilemma is to reduce management drastically by giving internal profit centers almost complete autonomy.

As Nicolai J. Foss says:

“Infusing hierarchies with elements of market control has become a much-used way of simultaneously increasing entrepreneurialism and motivation of firms.”15

But he also warns of the danger of managers taking away autonomy when convenient:

“… Frequent managerial meddling with delegated rights led to a severe loss of motivation, and arguably caused the change to a more structured organization.”16

When implemented appropriately, the result is an organization with many small profit centers that bring ideas to the market while being compensated appropriately. These profit centers are self organized to the extent that they have no higher central planner outside of themselves for their main idea. They must, however, settle any conflicts about any shared resources with other profit centers. These conflicts can resolved by central planning or by more self organizational techniques.

Complex Organization -> Efficiently Organized Smaller Entities

A complex organization is the structure of many small units under a larger umbrella at the top level. The complexity of the organization arises from the need to resolve problems of competition and cooperation among the smaller units. Cooperative problems tend to be related to resource allocation, coordination, and control. David Besanko describes a networked organization as one in which control is split into profit and responsibility centers. As the number of these smaller centers increase, large organizations struggle with the problem of how to organize across profit centers who may have different or competing incentive systems. Network organizations coordinate by elevating the focus of the individual or worker groups above the tasks they accomplish. Besanko says:

“The basic unit of design in the network structure is the worker rather than the specified job or task …networks develop from the patterned relationships of organizational subgroups”.17

Although network based organizations have high coordination costs, they can make up for those costs by being able to handle more complex information flows. Furthermore, Besanko et al. describe how modular network organizations operate as:

“… a type of network structure that involves relatively self contained organizational subunits tied together through a technology that focuses on standardized linkages. Most of the critical activities for a modular subunit are contained within that unit, and links with the broader organization are minimized.”18

The effect for the network in general is the reduction of search, monitoring, and control costs. Some network structures have the properties of a self-organized groups as noted:

“A similar network structure developed in SAP AG … one of the world’s largest software producers … To accomplish its growth objectives, SAP has developed a network organization of partners, who perform 80 to 90 percent of the consulting implementation business generated by SAP products.”19

The partners in SAP’s network operate as autonomous profit centers with SAP AG as the resource (product) owner in a stratified self-organized group.

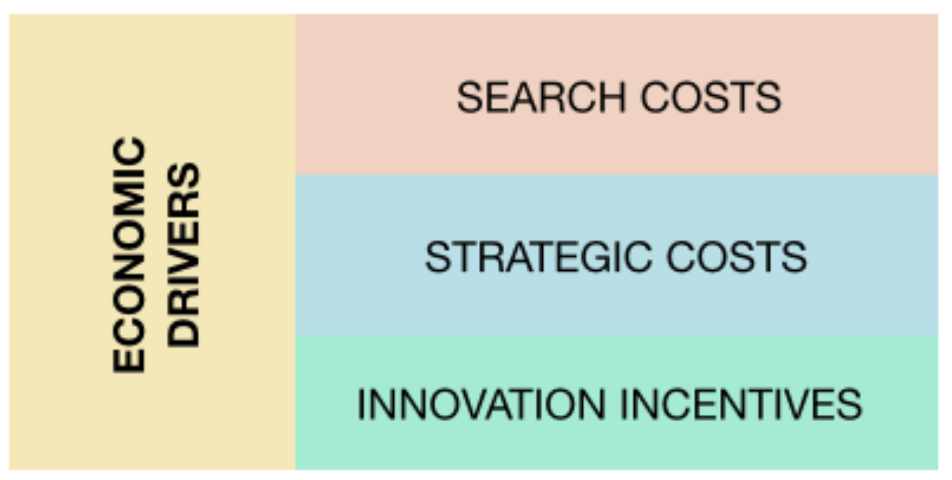

Worker Directed <> Worker Owned <> Worker Managed <> Cooperative

Without proper ownership and property rights, a harvestocracy20 can emerge. Examining the four types of ownership structures can help predict what type of self-organized group, if any, emerges.

One definition of a cooperative is “a jointly owned enterprise engaging in the production or distribution of goods or the supplying of services, operated by its members for their mutual benefit..”21 Having said that, Richard Wolfe reminds us:

“Cooperative ownership, cooperative purchasing, cooperative selling, and cooperative labor have all been called co-ops.”22

This implies that cooperatives are not necessarily worker owned, worker managed, or worker directed.

Workers can own the organization through company shares:

“When workers partly or completely own the corporate enterprises in which they work, they occupy a position like that of other shareholders …”23

But even then a worker in a worker owned business may not have enough ownership to mandate a directorial vote, in which case they are in a similar position to a minority shareholder in a regular corporation.

Workers can self organize and manage themselves but still be at risk of an inferior position:

“Workers who self-manage still function to execute the basic enterprise decisions made elsewhere by the directors. Worker managed businesses aren’t necessarily worker-directed.”24

Richard Wolfe describes a worker directed business as one in which:

“… no separate group of persons—no individual who does not participate in the productive work of the enterprise—can be a member of the board of directors. Even if there were to be shareholders of a WDSE, they would not have the power to elect the directors. Instead, all of the workers who produce the surplus generated inside the enterprise function collectively to appropriate and distribute it. They alone compose the board of directors.”

Autonomy + Economic Environment + Ownership Structure -> Self Organized Structure

Self organized structures are especially efficient when information flows become numerous. Large companies such as Mondragon in Spain and JP Lewis25 in the United Kingdom have been operating as a25 republic style self organizational structure for a number of years. The Underground Railroad and Request for Comment (RFC) standard are closer to a pure self organization. Certain external environments drive strategy, which invoke a response that takes the form of the structure of self-organized groups. When a self organized group is formed with the proper ownership and directorial rules it can restrict the emergence of centralized planning.

- Camazine, Deneubourg, Franks, Sneyd, Theraulaz, Bonabeau, Self-Organization in Biological Systems, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-11624-5 — ISBN 0-691-01211-3, (pbk.) p.8

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feudalism_in_England

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic

- Making Mondragon: The growth and dynamics of the worker cooperative complex, 1991, William Whyte, Kathleen Whyte, p. 35

- The Origins of Inequality: Insiders, Outsiders, Elites, and Commoners, Gregory K. Dow, Clyde G. Reed, Journal of Political Economy, 2013, vol 121, no. 3

- “Although all miners were well armed, there is little evidence of violence in the gold fields. There is also no evidence that specialized gunfighters were hired or that unusual abilities were in the use of violence were important”, Ibid.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underground_Railroad#Structure

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Request_for_Comments

- “The Internet Engineering Task Force is a loosely self-organized group of people who make technical and other contributions to the engineering and evolution of the Internet and its technologies.”, https://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1718.txt

- Coase, Ronald (1937). “The Nature of the Firm”. Economica (Blackwell Publishing)4 (16): 386–405.

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko [et al.] — 4th ed., p.527

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structure_follows_strategy

- “The formal hierarchical structures of organizations can be expected to affect the organizations’ behavior in many different ways. One kind of impact is that their structures may affect how their knowledge is organized.” Journal of Theoretical Politics October 2007 vol. 19 no. 4 425-463

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Innovator%27s_Dilemma

- Selective Intervention and Internal Hybrids, Nicolai J. Foss, Organization Science, 2003, Vol 14, No. 3 pp 331

- Selective Intervention and Internal Hybrids, Nicolai J. Foss, Organization Science, 2003, Vol 14, No. 3 pp 33

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko [et al.] — 4th ed., p.522

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko [et al.] — 4th ed., p.523

- Economics of Strategy, David Besanko [et al.] — 4th ed., p.531

- Watson, W. (2016), Harvestocracy, https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/vulk-blog/Harvestocracy.pdf

- http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/cooperative?s=t

- Wolff, Richard D. (2012-10-02). Democracy at Work (Kindle Locations 1590-1591). Haymarket Books. Kindle Edition.

- Wolff, Richard D. (2012-10-02). Democracy at Work (Kindle Location 1554). Haymarket Books. Kindle Edition.

- Wolff, Richard D. (2012-10-02). Democracy at Work (Kindle Locations 1577-1578). Haymarket Books. Kindle Edition.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Lewis_Partnership

Copyright © 2016 W. Watson, Vulk LLC All Rights Reserved